On August 9, 2014, the town of Ferguson, Missouri was thrust into the international spotlight when Officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown, an 18-yr old unarmed young black man. That event set in motion months of protests, peaking when it was announced last Monday night that a Grand Jury would not indict Officer Wilson.

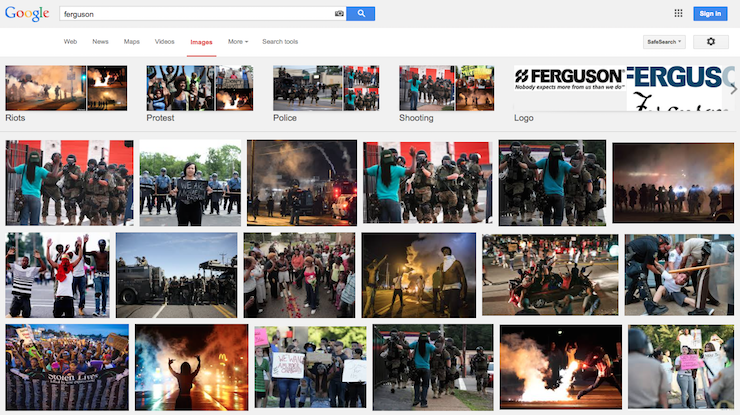

If you search Google Images for Ferguson, I’m fairly certain that residents wouldn’t have guessed their town would ever look like this:

Other than sharing some articles that I’ve thought were worth reading, I haven’t written anything publicly about Ferguson. And that’s probably for a variety of reasons. First of all, I just don’t know where to start. Second, I’m very aware that some of the advice that I’ve been hearing from folks – and I think it’s good advice – is that there are many white people who need to talk less and listen more, when it comes to racial injustice and race issues in our country. Third, serving a church that is fairly theologically diverse, I know that there are some folks who will agree with some my points below, and others who may not. However, I think it’s important to have these conversations – so this is my way of creating space for this discussion. Finally, there have been so many really good things written, I didn’t think that I’d have anything new to offer to the discussion.

I still don’t know exactly where to start – but I did want to offer a few thing that I’ve been thinking about after reading some of the articles that many people may have seen linked to on Facebook and Twitter. But first, a disclaimer. I’m going to post links to lots of articles below. As is the case anytime I post a link to an article on Facebook or Twitter, just because I link to a specific article doesn’t mean that I agree with everything that the author writes in the article.Â

Before sharing some of my thoughts, I wanted to share this video with you. Rev. Jevon Caldwell Gross is Pastor of St. Mark’s United Methodist Church in Montclair, NJ, and a friend from seminary. I ran across a sermon he preached back on Martin Luther King Jr. Day of this year at Kalamazoo College; I think his message is very timely and encourage you to watch the sermon.

So, What is Ferguson?

Ferguson is the death of a young man – a death that came far too soon – a death that was the result of a series of events I doubt we will ever fully understand or know. Officer Wilson has one story, others saw something very different, and we will never know Michael Brown’s version of what transpired. Ferguson is a tragedy of the worst kind for Michael Brown’s family – a tragedy that only someone who’s own child has died can even begin to comprehend. There is no future for Michael Brown and his family is forever changed.

Ferguson is also an awakening to the reality that we are not the country that many think we are. We are not a place where black and brown children have the same opportunities and life experiences that white kids do. We are not a place where everyone is treated equally by police officers. As much as we like to think we’ve moved far beyond the racial tensions during that led to the civil rights movement…if you talk to black young men and women about their experiences of living in the United States…I think you’d hear a different story.

Ferguson is also moving beyond a moment – to a movement. Ferguson is a movement of those who have been telling us for far too long that #BlackLivesMatter and yet, no one has been listening. Ferguson is a rallying cry for those who are calling for change; not change in an existential-wouldn’t-it-be-nice-if-things-changed kind of way, and not change in a Kumbayah-let’s-all-hold-hands-and-get-along kind of way, but change in an every-police-officer-should-be-required-to-wear-a-body-camera kind of way, or let’s actually change the laws, if it was the law (although a very questionable following of it – there were many things unusual about it) that allowed Darren Wilson to not be indicted.

We Need to Preach About Ferguson

We all know the adage that pastors should preach with a Bible in one hand, and a newspaper in the other. Well, that’s certainly true now more than ever – I’m guessing/hoping that many pastors will be preaching on Ferguson tomorrow. Our faith should be what is leading us toward pursuing justice and racial equality in our country and our world. And while we certainly live in a post-Christendom world, and the church has significantly less cultural clout than it once did, faith leaders from all religious backgrounds still need to be at the front lines of this movement – and help provide opportunities for reflection and conversation for our faith communities.

I Participate in Self-Segregation

This is not something I like to admit, but I think that I, and many others, do participate in this form of self-segregation talked about in the article, “Self-Segregation: Why It’s So Hard for Whites to Understand Ferguson.” The article states that the social networks of whites are 91% white – and this certainly affects the news that we get, and the perspectives that we hear from. And as I have browsed through my Facebook News Feed over the past week or two, I’ve noticed how true that is for myself. I’ve had to be much more intentional about seeking out black and brown voices to listen to. Some of the new voices that are filling up my Twitter stream include: Christena Cleveland, W. Kamau Bell, Yolanda Pierce, Ta-Nehesi Coates, Chaz Howard, Otis Moss III, Jonathan L. Walton, Syreeta McFadden, Efrem Smith, Cornel West and others.

As I prepare to return back to a very white suburban area of Chicago’s North Shore, I want to begin to think more proactively about how I (and how we as a church) can seek out relationships with our black brothers and sisters. Relating to one another will give us a chance to hear stories and have a small understanding of what our various life experiences have been.

Nonviolence versus Violence

I need to start by saying that I’m always in favor of nonviolence as a tool for resisting, protesting and trying to bring about change. And I’ve heard many friends, pastors and theologians (both black and white) speaking out and encouraging nonviolence. And I think that’s probably the best way to go about pursuing change. But here’s the thing. I extol the virtues and benefits of nonviolence as a privileged white person never having experienced oppression.

Growing up with a strong dose of Mennonite pacifism, that’s still the direction I lean, but I think it’s a much more nuanced conversation when it comes to nonviolence versus violence. Reading some of the articles below, it helped me see some of the nuances. When we talk about nonviolence, we often look back to Martin Luther King, Jr. and the ways in which he nonviolently resisted segregation and racial inequalities. Ta-Nehisi Coates, a senior editor for The Atlantic, wrote in his article, “Barack Obama, Ferguson, and the Evidence of Things Unsaid” that:

“What clearly cannot be said is that American society’s affection for nonviolence is notional. What cannot be said is that American society’s admiration for Martin Luther King Jr. increases with distance, that the movement he led was bugged, smeared, harassed, and attacked by the same country that now celebrates him. King had the courage to condemn not merely the violence of blacks, nor the violence of the Klan, but the violence of the American state itself.”

In another article, we are reminded that violent protests and riots have been key elements in some significant moments of social change in America.

Jonathan Walton, Professor at Harvard Divinity School and minister in the Memorial Church at Harvard University, also spoke about the power of protests in his article, “After Ferguson, When Will We Listen:”

Jonathan Walton, Professor at Harvard Divinity School and minister in the Memorial Church at Harvard University, also spoke about the power of protests in his article, “After Ferguson, When Will We Listen:”

“America must come to realize that protests, public outrage, and even rioting do not emerge out of thin air. Millions are not hallucinating. There are conditions in our society that terrorize and dehumanize people of color and the poor every day. Thus, until America wakes up and pays attention, we will be right back here in a few months in another city. Dr. King was correct that ‘a riot is the language of the unheard.’Â Right now the people of Ferguson are speaking. Will America listen?”

The only experience that I have with any type of violent resistance is when I attended a demonstration in Bil’in in 2005 when I was in Israel and Palestine. I wrote a bit about my experience of getting tear-gassed and hit with flash bangs (they called them shock bombs) here, and also reflected a bit about stone-throwing by Palestinian youth. I know this is a very difficult conversation – and I certainly never thought that I would consider even the potential for legitimizing violent responses and protests, but the reality is that I have never been oppressed and dehumanized in the ways that many others have been – and so it’s difficult for me to know how I would respond. I hope for nonviolence whenever possible, but realize that there may be times when violent resistance or demonstrations may be necessary.

In her article, “Ferguson, goddamn: No indictment for Darren Wilson is no surprise. This is why we protest,” Syreeta McFadden writes the following:

“And so we protest. Because it is our only recourse. We do not explode in violence, but we do not accept these terms that anticipate and perpetuate failure. We channel a sustained, clear-eyed rage, and we insist that our policies and our enactment of those policies ensure equal protection for the most vulnerable among us and accountability for officers in uniform when they kill unarmed youth with impunity.

“We protest so that some day, some years from now, justice is not a surprise, nor a dream, nor deferred. So that justice just is.”

What would you do for justice? What would you to help bring about lasting change and the reality of justice for all? For those of us who haven’t been in a situation where we were having to fight for justice (and I certainly haven’t been), I think it’s impossible to know what that really feels like, and to what extents one might go to achieve justice.

I’m Not Black – So I’ll Never Know

This isn’t news to any of you – but I’m not black. Never have been – never will be. I’m white. And with that comes privilege, white privilege, and the assurance that I will not have the same experiences as my black brothers and sisters when I run into a police officer. Or when I get pulled over on the freeway. Or when I walk into a gas station in the winter with my hoodie up and scarf wrapped around my face.

This isn’t news to any of you – but I’m not black. Never have been – never will be. I’m white. And with that comes privilege, white privilege, and the assurance that I will not have the same experiences as my black brothers and sisters when I run into a police officer. Or when I get pulled over on the freeway. Or when I walk into a gas station in the winter with my hoodie up and scarf wrapped around my face.

New York State Senator, Cory Booker, shared this week an article that he wrote back in 1992 after the Los Angeles Riots. In that article, he writes:

“TURN OFF THE ENGINE! PUT YOUR KEYS, DRIVER‘S LICENSE, REGISTRATION AND INSURANCE ON THE HOOD NOW! PUT YOUR HANDS ON THE STEERING WHEEL AND DON‘T EVEN THINK OF MOVING!â€

Five police cars. Six officers surrounded my car, guns ready. Thirty minutes I sat, praying and shaking, only interrupted by the command, “I SAID, DON‘T MOVE!â€

Finally, “Everything checks out, you can go.†Sheepishly I asked why. “Oh, you fit the description of a car thief.â€

Not Guilty…Not Shocked—Why Not?

In the jewelry store, they lock the case when I walk in.

In the shoe store, they help the white man who walks in after me.

That is not my experience – and it will never be.

No matter how hard I try, how many conversations I have with black and brown friends, I will never know what it’s like to be black or brown in the United States.

That’s frustrating as someone who would like to understand better. But it is also humbling, and a reminder that I need to be doing a lot more listening than speaking.

Ferguson is About Racism/Racial Injustice

There are some who say that Ferguson is not about race: it’s a simple story about a cop who did what was necessary because he was afraid for his life. Have you heard people say that? You probably have. And the people who are saying that are probably white. The one black person that critiqued the initial rush back in August to call this a “race” issue was Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. But it’s pretty clear that he’s changed his thoughts about the issue after reading his most recent article in TIME: “White People Feel Targeted by the Ferguson Protests—Welcome to Our World:”

“Many white people think that these cries of outrage over racism by African Americans are directed at them, which makes them frightened, defensive, and equally outraged. They feel like they are being blamed for a problem that’s been going on for many decades, even centuries. They feel they are being singled out because of the color of their skin, rather than any actions they’ve taken. They are angry at the injustice. And rightfully so. Why should they be attacked and blamed for something they didn’t do?

“Which is exactly how black people feel.”

When a 6’4″ and 210lb police officer describes an altercation with another young man who is also 6’4″ by saying that he felt like he was a 5 year old boy holding onto Hulk Hogan, and described him as a “demon” – one has to imagine that there are race issues at play. There was certainly a culture with racial tensions that provided the background for how Officer Wilson could look at Michael Brown and consider him an “other” – a demon – someone that wasn’t even really a person – but from the statements that he made – almost a demonic force – but certainly not a human he viewed as his equal.

Will We Ever See Justice?

In a guest post on Tony Jones’s blog, Anthony Smith, also known as postmodernegro, wrote about whether or not we will see justice in our world when it comes to issues around racism and racial equality. In his post, “Justice is Possible” he plays with an interesting thought experiment with Jacques Derrida and Margus Garvey, in which he concludes that:

“This thought stuck to me: suppose racial justice in America will forever be an eternal possibility. Only a possibility. Never to cross over wholly into the event horizon of actuality.

“Before last night I thought there would be no indictment and that we would soldier on, organizing and protesting and calling the Powers into account. But after it was said and done, my soul conjured the thought of the possibility that racial justice in America will forever and eternally be a possibility. A world without end.”

I can appreciate the fact that it does feel like justice will be an eternal possibility – and I think Anthony would have a better sense of that than I would, but like my buddy John Vest, I have to have hope that we will see a more realized justice in our world. Most of the time, it doesn’t look like it could be a reality. Most of the time, it looks like people will continue to be the broken, selfish people that we are.

But every now and then…every now and then we can see a glimmer of hope. Of clergy and young black activists and men and women from around the country (and world) coming together to show Ferguson that they stand with them. Hope. I think to be engaged in this important work – you have to have hope. Or at least fake it and have faith that the hope of others can carry you on.

What Now?

Honestly? I’m not sure.

I know that we need to pray. I know that we need to develop relationships with new people. I know that we need to talk with our children and youth about Ferguson. I know that we need to talk with our congregations about Ferguson (I’m grateful that the Episcopal Church has provided some resources for doing so with churches and other resources specifically for working with children and youth).

I know that we need to insist that our law enforcement officers are held to the highest standard possible. Yes, they are risking their lives daily to serve and protect the American people. And I realize that I’m not doing that every day. But we must take whatever steps are needed to ensure that our officers truly are serving and protecting everyone. When a cop can pull up to a park and gun down a 12-year old boy in Cleveland within seconds of getting out of his squad car…something is seriously wrong.

But more than anything…I think the call for white Americans right now is to listen. And yes, I realize the irony of that after writing a 2,500 word blog post.

But before we have the right to speak, I think we have some serious listening to do.